How do we report?

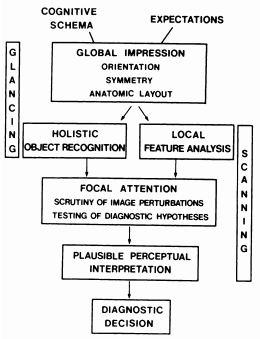

Reporting is a visual task. Nodine and Kundel proposed that there were two phases of visual search – global and focal – followed by a decision-making phase.

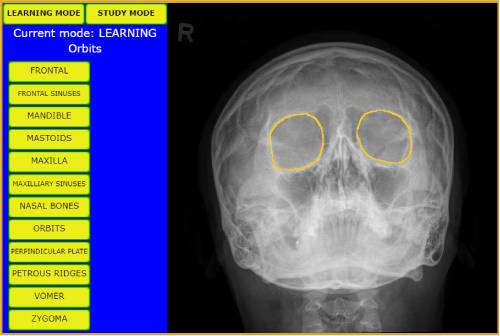

Global Impression

This initial phase of search relies on pop-out detection. A quick scan of the image is compared against reader’s mental map of normality and any feature which is not consistent with this idea of normality should “pop out”. This is also referred to as heuristical thinking (A heuristic is a mental shortcut that allows rapid problem solving based on assumptions and past experiences).

Any areas of the image which do not conform to the normal mental model are noted for closer consideration on the second pass and a preliminary hypothesis is formed, free from biases which may be introduced by the referral and any previous reports. This entire process should happen prior to reading the clinical information provided by the referrer and should last only a few moments.

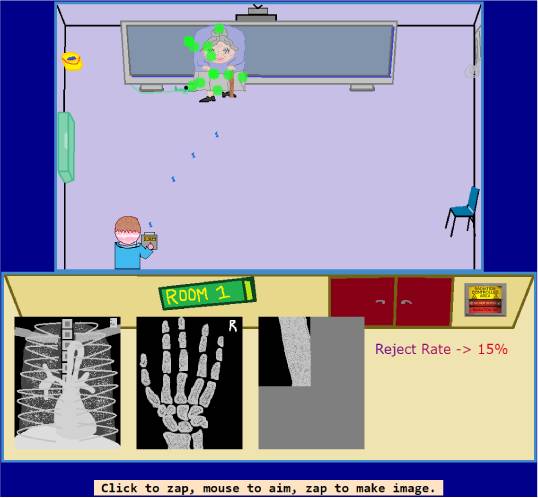

Focal Attention

After reading the referral, which of course will provide a detailed clinical history and conclude with a question to be answered, the reader scrutinises the image methodically. The eye is directed around the image, pausing on each area of interest until the reader is satisfied that no more useful information remains to inform the consequent decision. Perceived “signals” are first either dismissed as artefact, irrelevant or normal variant, or otherwise included as positive findings which will inform decision making.

While every image will be examined methodically, the information provided by the referrer will help us to identify “review areas” for closest inspection:

Examples:

- If a patient with known osteoporosis has sudden onset metatarsal pain following a step aerobics session, we will closely examine the specified painful area for evidence of stress fracture.

- If a patient with diabetes has a non-healing ulcer on the foot, we will closely examine the bony anatomy adjacent to the ulcer for evidence of acute osteomyelitis. We will also be on the alert for other diabetes related MSK pathology, like Charcot arthropathy.

- If a patient with chronic kidney disease presents with severe pain, swelling, redness and warmth of a joint, we will be on the lookout for gouty tophi and bony erosions at the affected joint.

- Specific mechanisms of injury may indicate close search of specific anatomical areas; FOOSH => scaphoid, inversion injury to the foot => base of 5th metatarsal and anterior calcaneal process, axial load to a flexed elbow => coronoid process

- Positive clinical tests may identify potential areas of bony injury; positive valgus/varus stress test of the knee => collateral ligament avulsions, positive Ottawa ankle assessment => likely ankle fracture.

For each specific anatomical series, we also have standard “review areas” where uncommon pathologies may be commonly missed, or where you as a reported have missed pathology previously:

Examples:

- AP shoulder => bony thorax

- AP pelvis => sacral foramina, L5/S1

- Facial bones => mandible

Access to previous imaging studies (either directly or via a previously well written report) help us to exclude chronic or incidental findings (such as accessory ossicles, remodelling deformities from previous bony injury, integrative appearances around arthroplasties and developmental anomalies), or to address a specific clinical question, such as change in fracture fragment position for a fracture clinic review. They also help us to include findings, such as progression of degenerative joint disease or the presence of a new bony lesion which may require further investigation.

Once the reader is satisfied that no further information remains to be gleaned the preliminary hypothesis is then tested against this “higher resolution” evidence.

Decision Making

We now take all the evidence from the radiographic “crime scene”, test against our hypotheses and come to one or more likely conclusions (i.e., a list of differential diagnoses - “The hoofbeats heard outside the window and recent government ban on donkey ownership likely indicate the presence of a horse, however given the close proximity of a zoo with a relaxed attitude to fence maintenance, the presence of a zebra cannot be entirely excluded”). We utilise all the information we have at our disposal to do so – the clinical history, previous imaging findings, our prior experience, preferred reference texts and so on – however we must be conscious that each of these tools introduce certain biases to our decision making which goes part way to explaining the phenomenon of interobserver variability in image interpretation.